THE NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN

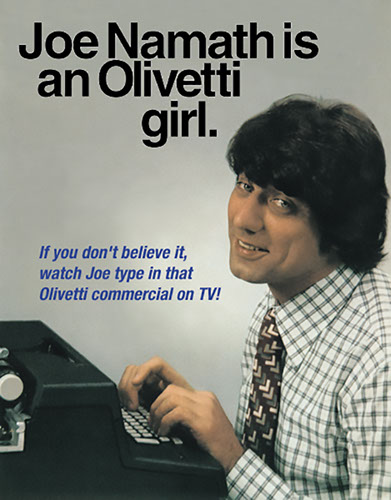

VERSUS BROADWAY JOE NAMATH.

The Olivetti campaign burst on the scene in 1972, just as the National Organization for Women (NOW) was flexing its muscles. NOW attacked the campaign for stereotyping women as underlings (they were furious that only men were shown as bosses while only women were shown as secretaries), and they called me a male chauvinist pig. They picketed the Olivetti building on Park Avenue and sent hecklers up to my office to un-n-n-nerve me. Something had to be done. Who can fight a woman’s fury? I capitulated. I would do an ad and a TV spot, with a woman executive giving orders to a male secretary. I cast an actual woman exec (not an actress) as the boss. I cast Jets great Joe Namath as the secretary (because he could type). I invited the women of NOW to view the spot, but when they saw the boss ask her secretary for a date at the conclusion of the spot, they were aghast. (You do very good work, Joseph. By the way, what are you doing for dinner tonight?) “It’s an old story,” I said. “The boss always tries to make the secretary.” They cursed me (I swear), walked out and never bothered this male chauvinist pig again.

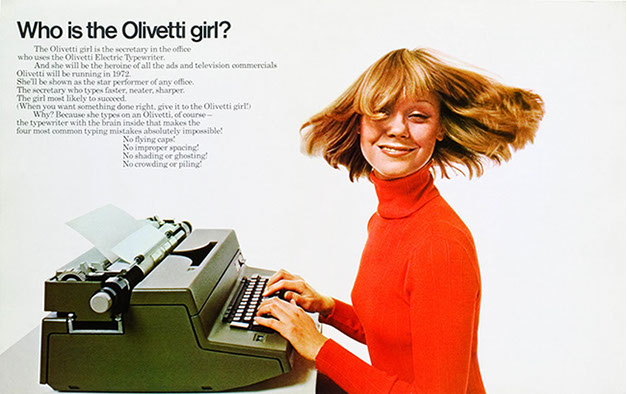

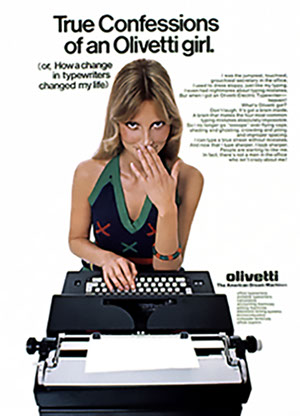

WE HAD TO MAKE THE OLIVETTI TYPEWRITER FAMOUS FOR SECRETARIES TO ACCEPT IT.

Olivetti, the great Italian typewriter, had been advertised in America with a primary emphasis on the beauty of its design. Among industrial design cognoscenti, Olivetti was always synonymous with beauty, but most people wouldn’t recognize good design if they tripped over it. Sales of Olivetti’s splendid line of electric typewriters had gone stagnant while mighty IBM had the market locked up. IBM was so dominant that purchasing agents of large corporations would rarely even consider buying another brand. We had to break through the IBM barrier. To plot our strategy, Jim Callaway interviewed many key buyers and found that while they regarded Olivetti as a top-notch typewriter, their hands were tied. Secretaries, they explained to Jim, felt that IBM gave them status. So we conceived the Olivetti Girl, who would out-status everyone. We told secretaries that Olivetti was the typewriter to type on. And we were putting across a message that was being seen by her boss, her girl friends, and all those reluctant purchasing agents. We produced six ads and nine TV spots that showed the Olivetti Girl as the star performer in her office, as the secretary who typed faster, neater, sharper, as the girl most I likely to succeed. (One of our headlines summed it up: “When you want to do something right, give it to the Olivetti Girl!”) In a few weeks, brand awareness of Olivetti leaped, and sales of Olivetti typewriters went through the roof.